Jonathan C. Lewis

Author and Artist

Charade

A fictional travelogue; four minutes to read.

The Beijing pedicab is a deep, rich, Chinese-flag red. The driver—he never tells me his name—is as spindly as a prepubescent ten-year-old. He wears skinny jeans and a thin blue sweater. His greying hair is trimmed in a buzz cut.

He is alert. Like a hovering hawk waiting for a kill to turn up. No book to read, no music headphones. No diversion from watchful waiting. His face is the expressionless mask of weariness. If I sink to stereotypes, inscrutable.

As I climb into his pedicab, before I am even seated, my driver asks about my age, marriage status, income. Taken aback, I stumble over a vague verbal retreat. As I learn later, in China polite conversation includes intrusive personal questions, except they’re not considered intrusive.

The unsettling thing about dropping into an entirely different civilization, in addition to not knowing the basic, everyday patterns of life, is not understanding how to read another person. Is a local woman’s smile a flirtation or an awkward timidity? Is a man’s lingering touch an overture or merely a soft handshake?

My driver half-smiles at my garbled reply. I can’t tell a warm smile from a mocking smile. When he looks away, what does it mean? Is he keeping his eyes on the roadway or rejecting me? I fall into a queasy quagmire of cultural ignorance.

With eight billion people living in it, the world is bursting with every imaginable custom, practice, belief, superstition. Tastes and textures, principles and non-principles, sexual practices and preferences, zealots for good and zealots for no reason at all. Every civilization offers something uniquely wonderful and sometimes something uniquely horrifying.

The continuing sermon of my classroom teaching, my life’s work, the career that I curated for myself, is tolerance and understanding. “Be open to new ideas, new perspectives, new experiences, new cultures.” That’s what I tell my high school students.

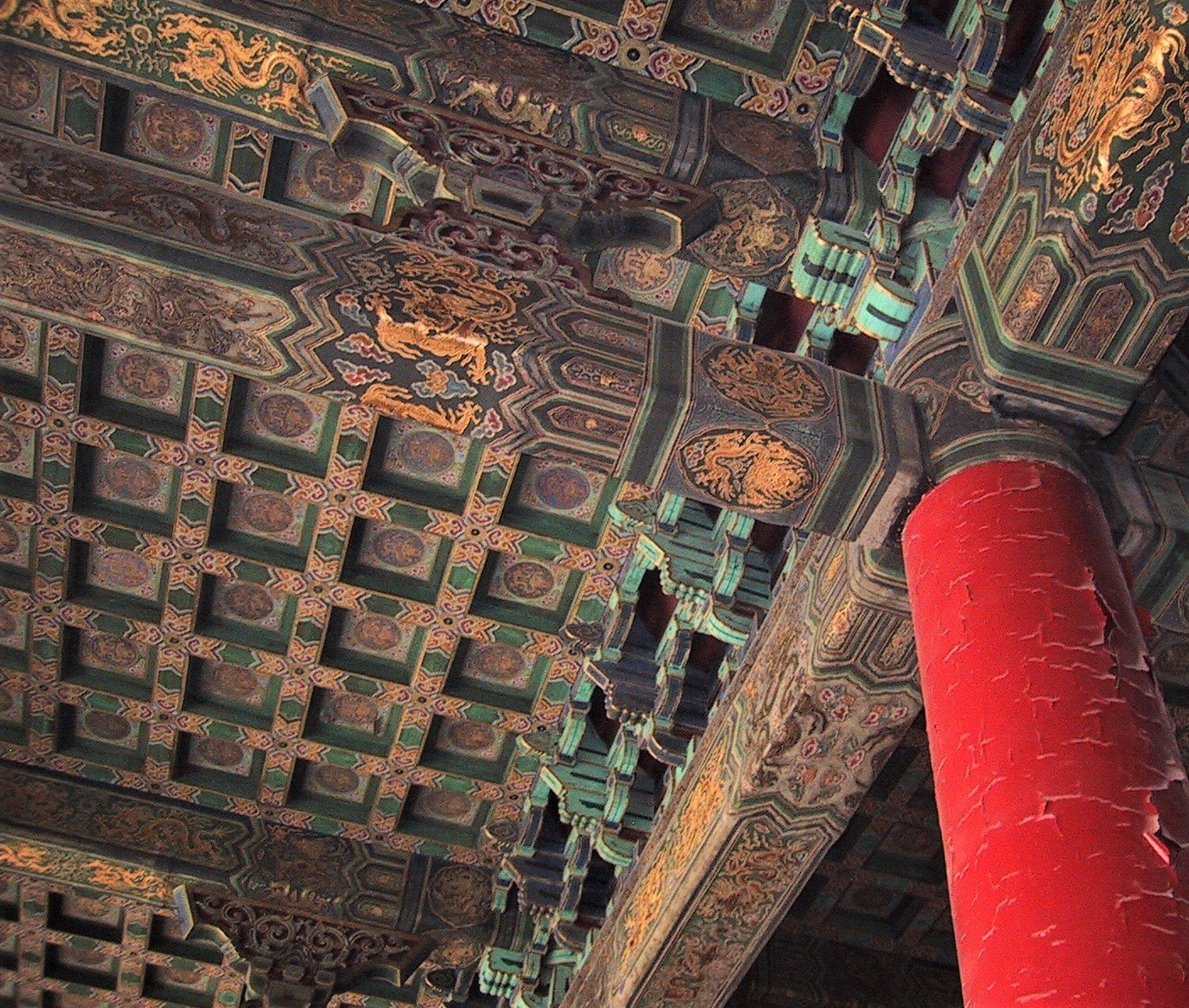

China is testing my charade. I’m only here to see temples with tiled roofs, landscaped gardens and quaint pagodas. I arrived in Beijing knowing something about ancient Chinese history, and nearly nothing about contemporary, everyday habits. I know enough to reject the urban legend that The Great Wall can be seen by astronauts or functioned as a military fortification, but that’s about it.

As nations go, China has a lot to answer for. Human rights abuses, censorship and mass social conformity churn my stomach. If the country were a person, it would be canceled. Instead, the world looks the other way because the alternative is war.

It also has a proud history. During the time of Genghis Khan, 13the century China destroyed feudal aristocracies in favor of meritocracy, created the world’s largest free-trade zone, abolished taxes for doctors, teachers, clerics and schools, established the world’s first international postal system, allowed for religious freedom, abolished torture, invented diplomatic immunity for ambassadors and innovated general literacy for the peasantry in public schools.

Only an arm’s length away, my driver is withdrawn, uninformative. Parks and palaces whiz by. Horse-drawn carts with large loads weave precariously between BMWs. My clumsy ignorance entombs me in a kinda Chinese golden amber.

At my hotel, I pay the pedicab fare, miscount the yuan, tip too much and swiftly withdraw into the cocooned safety of my American hotel room to watch English-speaking television.