Jonathan C. Lewis

Author and Artist

Chinatown

A fictional travelogue; four minutes to read.

Forty-eight years ago, I was born in San Francisco. My neighborhood was quiet, sedate, inward.

In the Sunset District—parochial, working-class, first- and second-generation Italians and Irish—the streets were lined with rows of pastel-colored bungalows with tidy gardens, drawn curtains and shuttered doors. People—busy bodies as much as Good Samaritans—looked out for each other. Like San Quentin prison guards, neighbors watched me grow up, informing my parents about my every antic—the car alarms I triggered, my first cigarette, the girls I tried to kiss.

To escape the prying eyes of the adult world, I embarked on my earliest travel adventures. By age twelve my spindly teenage legs were taking me to neighborhoods not my own.

In search of privacy, I trekked busy boulevards, gawked at tony mansions, poked into tawdry bodegas, traversed Golden Gate Park, climbed hilly steps headed towards the stars. Every shop window was a museum case. Municipal buses were 747-airliners soaring over mountains and into cloudy vistas, flying through the turbulence caused by potholed streets.

Sooner or later, I arrived at Chinatown—the first of many visits. In thirty-square blocks, 70,000 people live, eat, do laundry, attend school, care for the elderly and entertain themselves.

People here walked together, shopped together, played together. The very old escorted the very young to school and back. Mothers and adult daughters strolled arm-in-arm. In community parks, men hovered around chess sets to wait their turn, murmur over brilliant moves, applaud the winners.

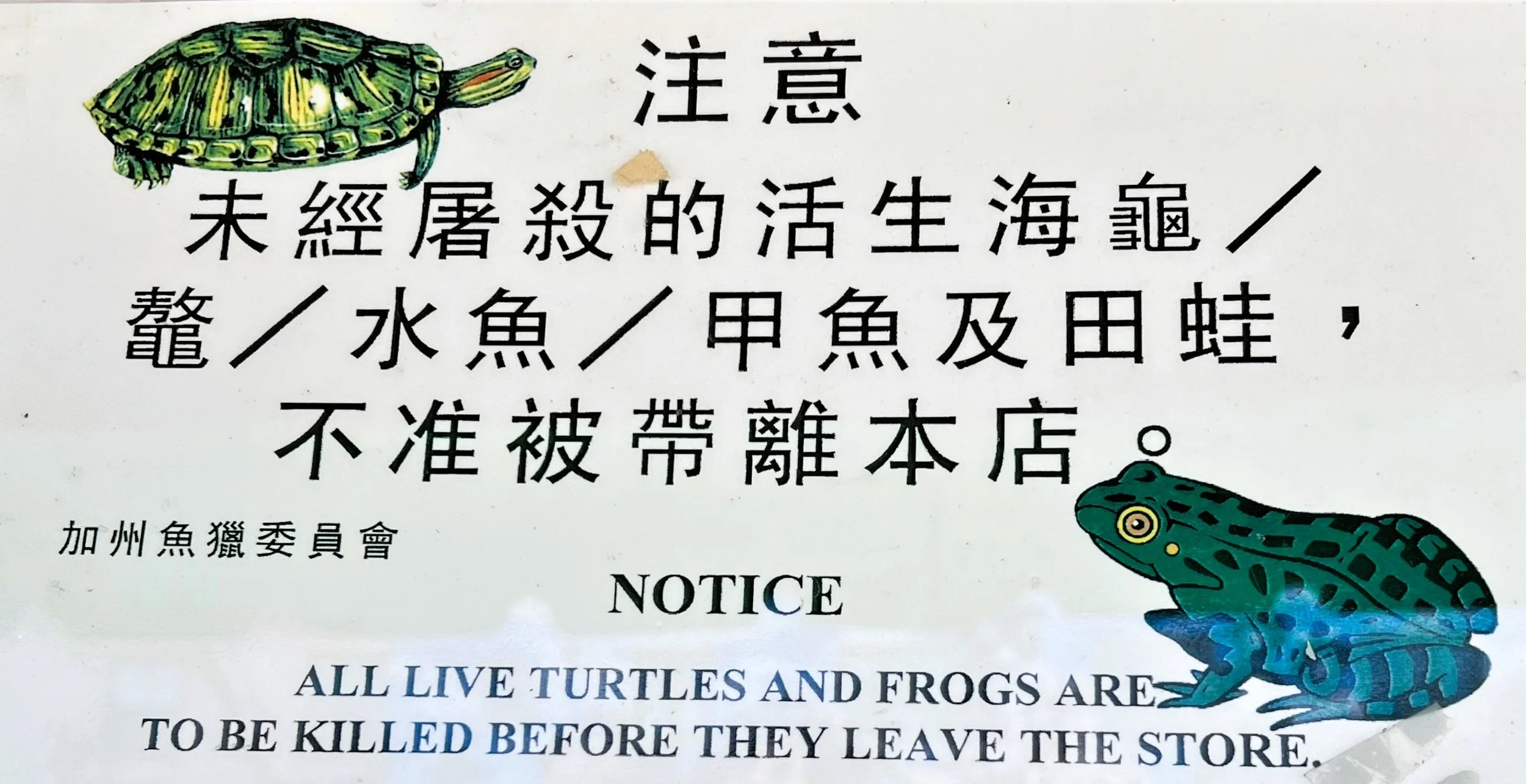

Chinatown is a chaotic mélange of markets selling fish fresh swimming in watery tanks, roasted, glazed chickens hanging from meat hooks, rows and racks of I-Love-Chinatown kitsch, exotic herbs and cures, hardware stores with woks, chopsticks and wood-handled ladles, crappy tee shirts made in China for American tourists (because who else would want them), Laughing Buddhas, tea in colorful tins, bins and buckets overflowing with strange vegetables, live bullfrogs ready for home cooking. I saw pagodas for the prayerful and dim sum eateries for the hungry. Laundry drying on balconies and scarlet red street lanterns swaying in the cool breezes coming off S.F. Bay.

For meals, I ate deep-fried chicken feet, but there’s nothing particularly delicate about eating toes. Lunch was unstoppably destined for my shirt front.

With the instant, instinctive wisdom of youth, in Chinatown I knew I was the perpetual outsider unable to fully unfold the layers of another culture. From sitting alone in the school cafeteria, I knew that outsider feeling all too well.

Walking down Ross Alley—built in 1849, the oldest alley in San Francisco—I headed to the Golden Gate Fortune Cookie Factory. The sweet, seductive, sensuous scent of cookie dough baking—an aroma which four decades later still lingers in my nostrils—enveloped me. On cast-iron grills, a handful of Chinese women cook 10,000 cookies a day, stuffing each folded cookie with fortunes written just for me. I devoured crisp, crumbly cookies until my tummy distended to Buddha-like proportions.

Far from the Sunset and my school studies, Chinatown was my first infatuation with the eroticism of the diverse. As if catching a chance smile from the prettiest girl on the playground, my last fortune from my final fortune cookie fluttered my stomach with warm excitement.

“Travel will be an important part of your life. Go with curiosity.”