Jonathan C. Lewis

Author and Artist

Cow Hollow

A fictional travelogue; four minutes to read.

Two women in their late twenties are sipping cappuccinos at a local coffee house on Chestnut Street, San Francisco. They are reassuring each other, proclaiming locally-owned, small businesses are their jam. I am at the table next to theirs, eavesdropping.

Just back from her European vacation, the woman wearing maroon yoga pants and matching fingernails is bitching to the woman wearing blue jeans and a white shirt about the scourge of McDonald’s throughout Italy. 54 outlets in Rome alone. Worldwide, 39,198 locations in 119 countries. They are, she complains, trampling local culture and commerce. She pronounces “McDonald’s” as if it were a bug she just spit out. In a perfect imitation of a bobblehead, the woman in jeans is nodding her head.

Despite her canting and carping, the woman in yoga pants is a walking billboard for globalization. Her sportswear is stitched in China. Her Apple watch assembled in Vietnam or Thailand. Her leather handbag is Italian. She is fragranced with a French perfume. Apparently, her concern for locally-owned enterprises has its epicurean limits.

She herself is an import. A gentrifer. A human Big Mac.

Before she and her ilk arrived, Chestnut Street was a drowsy, laidback neighborhood with a mom-and-pop bodega, a single screen movie house, one pharmacy, the ‘original’ Original Joe’s Italian restaurant, an indie bookstore, a record shop, a dry cleaner. Now it is her retail playground—a five-block souq of fashionable boutiques, trendy restaurants, Pilates studios, wine bars and pricey bakeries.

After the 1906 Earthquake, debris and detritus was dumped into S.F. Bay to create 636 acres for a world’s fair. The 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition celebrated the opening of the Panama Canal to international shipping and global economic interdependence. The Palace of Fine Arts—the city’s most romantic picnic spot—is the fairground’s legacy building.

Whether Ms. Maroon Pants would have picketed the fair, I will never know. Probably.

Long before the Exposition, cows wandered sand dunes, grazed on grasslands and drank from a picturesque lagoon. Dairy farming eventually gave way to light industry and housing developments, but the Cow Hollow nickname survives. Like naming a street with only imaginary chestnut trees Chestnut Street.

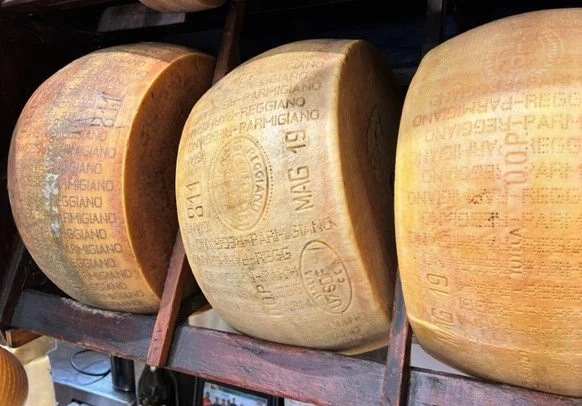

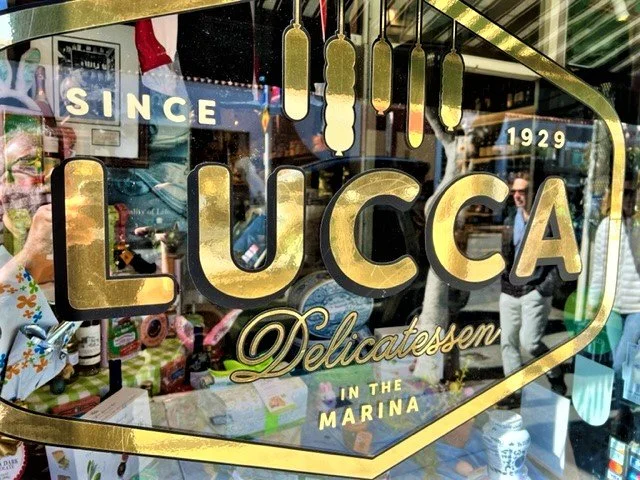

On Chestnut Street, Lucca Italian delicatessen, opened in 1929, is the real deal. Imported Italian foods are shoved into a space no bigger than a tramway gondola in the Italian Alps.

Salamis hang from the ceiling. Tilted upright, large wheels of cheese. Handmade breadsticks—gnarled like tree limbs—are stacked helter-skelter in a bin. A glass candy jar crammed with kosher pickles. Sardines swimming in virgin olive oil. Balsamic vinegar, fresh-carved turkey, bread rolls, pepperoncini, ravioli, potato salad, Cerignola olives.

Every morsel on offer in Lucca comes to me via the Panama Canal on cargo ships steaming under the Golden Gate Bridge. Even the name Lucca is ‘imported’ from the northern Italian town of the same name.

Almost certainly, Ms. Yoga Pants and her girlfriend in jeans shop at Lucca’s. It’s the trendy thing to do.

McLucca’s.