Jonathan C. Lewis

Author and Artist

Death of a Waitress

A fictional travelogue; four minutes to read.

Dear Travel Journey,

At the Fowler Museum in Los Angeles, in the middle of a quadrangle of galleries, sheltered by a portico, there’s a cozy courtyard with a life-affirming, gurgling fountain. I’m resting here, reflecting on my day.

In Los Angeles, black is the spirit color of waiters and waitresses. Apparently, restaurant owners think it’s chic to dress their servers in the color of death. Personally, I’d prefer cheerier colors with my tuna sandwich.

At lunch, before I taxied to the Fowler, my waitress—wearing black jeans, black blouse, black hairband and a name tag in black letters reading Charlotte—was not much on small talk. As if carrying plate of food and breathing is all that she could handle.

Taking my lunch order, her gravelly voice reverberated from deep in the back of her thin-lipped mouth, a mouth nearly hidden by deeply grooved facial wrinkles. On her break, through the restaurant window I saw her killing herself in the parking lot with a cigarette, puffing in the nicotine in long, pleasurable inhales.

When I paid my bill, I fought back the urge to say something about her smoking. It was none of my business, and nothing about her suggested she wanted anyone else’s opinion about anything at all, let alone her health habits.

There’s no acceptable norm for suggesting to a stranger “give up smoking.” It’s not the same as saying “have a nice day.” Like a muzzled tourist without permission to comment on a cultural custom or local practice, I said nothing.

On the road, time and again, I rediscover the human inclination to help another human, to save a life, is basic—a survival instinct essential for tribal preservation, for global citizenship. Even in Hollywood, we are social animals for more important reasons than gossipy entertainment.

Here at the museum in the first gallery, Australian aboriginal textiles exploded my optic nerves with color. The fabrics would make spirited shirts and blouses for the best of restaurants.

In another room, a profusion of ritual masks, burial objects, votive offerings from every continent united in a pulsing, almost panicky search for death’s meaning. I thought about my waitress.

A ghostly vision of her balancing plates of food on outstretched arms flashed in front of my eyes. A priestess praying. Or perhaps carrying entrails into a temple. On her head, a coffin.

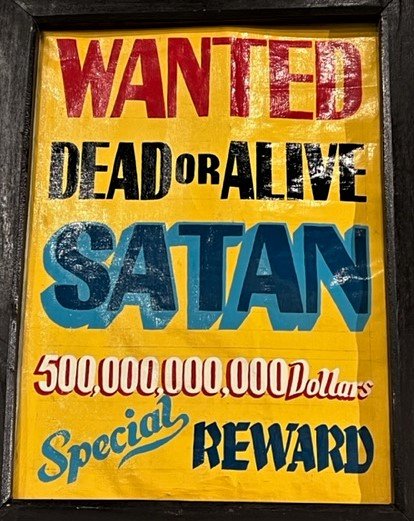

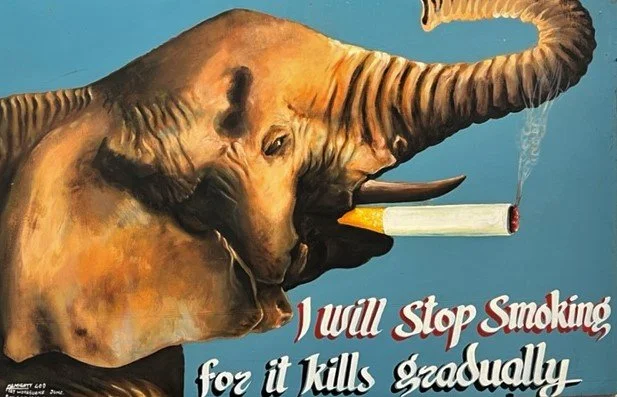

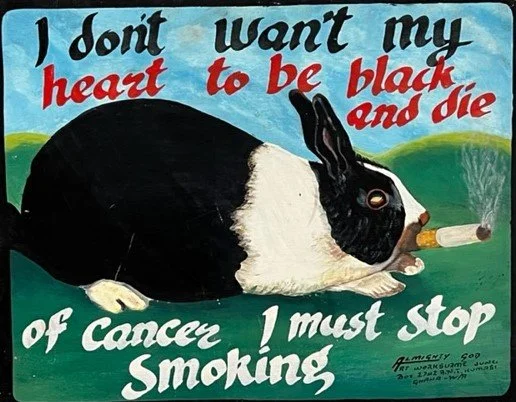

In my reverie, my waitress visits the museum exhibit by Ghanaian artist Kwame Akoto. Against a backdrop grisly graphic imagery, his pieces—as subtle as a lightning strike to the skull—sloganeer in plain English: “Stop smoking. It kills gradually.” And, “I don’t want…to die. I must stop smoking. Perhaps if my waitress could just see his work, she would see a sign, a prophecy, about herself.

Life regrets pile up. Standing on shore watching a drowning. Not stopping to help at a roadside accident. Failing to report a drunk driver. Not calling out a barroom bully. Not talking to a stranger.

While I collect my thoughts, my obligations and my indifferences, the societal and cultural boundaries separated me from my waitress, my chest tightens. A cigarette-sized part of me dies.