Jonathan C. Lewis

Author and Artist

Forgettable, But Not Forgotten

A fictional travelogue; four minutes to read.

On the outskirts of Budapest, my taxi driver pulls to a stop in front of an unadorned path, lets me out, then hurriedly drives off. He’s anxious to get back to the touristed part of town. Scanning the desolate streetscape, I think I have been dumped at the wrong address, but there’s no mistake.

Memento Park is on the outskirts of Budapest. Out of sight. Out of the way. Far from the sightseeing tour buses.

The entry is a small kiosk staffed by a lone and somewhat disheveled ticket taker. As I approach, he barely moves. Like a Kremlin policeman, he doesn’t appear to recognize my existence.

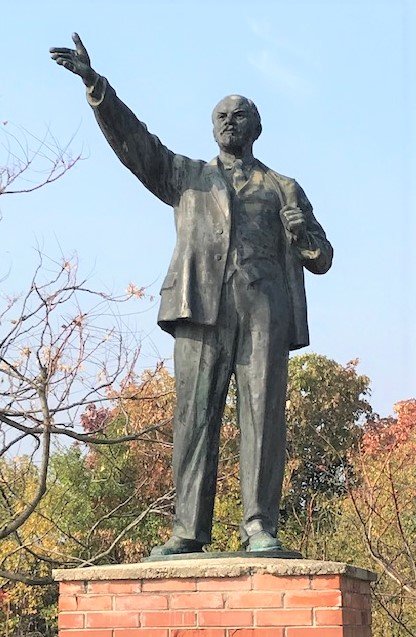

After the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, Soviet-era statues throughout Budapest were dethroned, then repositioned to Memento Park—a scruffy, weedy, open-air museum. Here history is preserved, but not praised. Disgraced, but not denied.

Under Soviet rule, WPA-style art projects showcased sturdy young Russians marching towards their futures, resolute soldiers headed to victorious wars and happy laborers toiling in fields or at machines. The monuments are bold, imposing, energetic, but difficult to love. The genre—brutal realism—propagandizes governmental lies with bombastic certitude. In desperate need of employment, talented Soviet sculptors set aside their principles to praise—creatively, if the word is used in its broadest sense—the utopian workers’ paradise.

If Michelangelo’s David depicts male beauty in repose, then the Russian artist Kiss István depicts male purpose in motion. Istvan’s dynamic, forceful, larger-than-life statute of a sailor races to join the fleet, or towards an idealistic future, or perhaps just to the nearest bathroom. I’ll never know. Perhaps I’ll ask my high school history students to write an essay on “Kiss István: Survivor or Sellout?”

Under the grey skies and blowy wind, a shiver strong-arms my body. As I trudge the gravel path, passing through the maze of trophies-turned-into-tombstones, I imagine statues of Hitler, Mussolini, Mao Tse Tung, confederate generals and Trump joining Lenin and Stalin.

Dishonest, propagandizing art is alienating, debasing, debilitating, corrosive, exhausting. Like coping with Trump’s daily dose of deceit, my breath quickens, my jaw clenches. The effort slimes me.

Returning to downtown Budapest, along the riverfront I am at a memorial and a gravesite—and a crime scene. Sixty pairs of iron shoes are forever fixed in place along an embankment near the Hungarian Parliament. The artwork is called Shoes on the Danube Bank.

During WWII, men, women and children—mostly Jews—were brought to the river’s edge, forced to remove their shoes, then shot. Plummeting into the Danube, their bodies floated downstream.

I bow my head, but I’m not praying. Images of human safety-seekers shoved into the Rio Grande blur with the Danube filled with human flotsam. My feet won’t move.

The history of Budapest is unscabbing my political wounds, scars, my fears. Anxieties about the woke and the unwoke, the far Left and the far Right knot my stomach. American Nazis, Trump cultists and selfish single-issue voters like the gun nuts and Gaza purists scare me. Dogmatically, I’m afraid of dogma.

Back in my hotel room, trying to nap, I’m awake with the sweats. My shoulders shudder. The sheets are as wet as the Danube.