Jonathan C. Lewis

Author and Artist

The Decent Docent

A fictional travelogue; four minutes to read.

If Pergamon Museum in Berlin charged admission, I’d demand a refund. Not wanting to risk overlooking a single one of the museum’s marquee artifacts, I am on the free, docent-led tour.

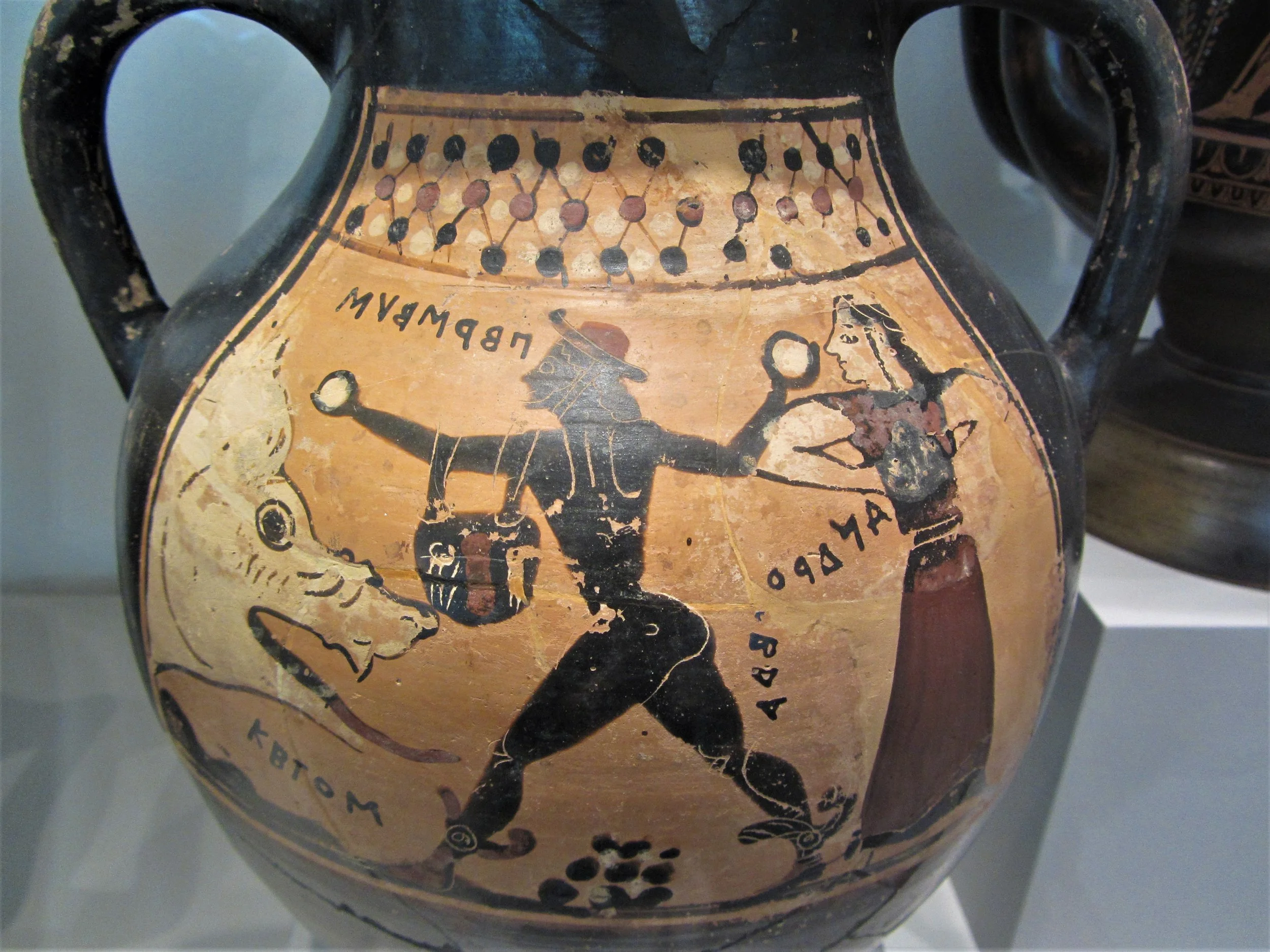

In the museum’s massive galleries, in the long hallways, in the side rooms tucked here and there, up and down flights of steps lined with ancient treasures, I’m in a souq overflowing with vases, statuary, Islamic decorative arts, archaeological treasures, artifacts, amphora, antiquities and artworks from ancient Greece, Rome, Mesopotamia, Syria, Anatolia. Pergamon is the summation of centuries of German exploration, exploitation, colonialization.

The docent’s name tag reads Lisbeth. No last name. She wears a floor-length skirt with an army fatigue pattern that’s no longer stylish. A taupe cotton blouse buttoned at the neck, hard-to-see earrings, hair in a tight bun, sensible shoes. Lipstick the color of sunburn. She carries herself with a serious amount of self-satisfaction.

When she talks, her eyes colorize from dull grey to a molten amber. Her scratchy, deep-pitched voice has a Spanish, born-in-Spain accent. She alternates between excavating the provenance of a particular antiquity and reciting a playlist of grievances about cultural appropriation and art theft.

A few minutes into the tour, I’m grinding my teeth.

Lisbeth, I am discovering, is a member in good standing of the fashionably offended. She takes her responsibility for my conscience seriously.

Usurping her transitory authority as an informational guide, she is turning the museum into a crime scene, indicting me and the other tourists in our group as criminal accessories after the fact. She wants us to know that the museum collection was assembled by white people, probably privileged with money and power and probably from colonialist countries. She does not invite discussion.

Lisbeth’s virtue signaling buzzkills any chance to enjoy, appreciate, respect ancient peoples and their magnificent civilizations. Distracted from focusing on the art and artifacts by her haranguing , my face reddens.

Her face—agitated by her fevered lecturing—has flushed crimson, matching my own. I wonder why she bothers herself to work in a place she finds so disreputable.

I also wonder why I just don’t leave the tour. I should say something, and then take my leave.

I should defend my belief in the universality of humankind. That great artworks belong to all of us. That a great museum is the world’s scrapbook.

Her rectitude does not consider that repatriating art might be a compounding sin. Where is the ‘museum justice’ in returning an object of high artistic value to an authoritarian country that stifles artistic freedom, free speech, free thinking?

She snuffs out, seemingly without a care, the notion that people, ideas, music, art should be borderless. Nobody gets to choose where they are born. Artists create artworks wherever they are because that is where they are.

Ancient artworks and archaeological digs don’t come with mattress tags reading “do not remove under penalty of law.” If a centuries ago an evil archaeologist did an evil thing, I’m content to overlook the transgression. No one is perfect, not even Lisbeth.

Indeed, I am tempted to tell Lisbeth that her world view, pushed to its logical limit, means a world in which she would be repatriated to Spain or Latin America or wherever she comes from. Hmm, maybe she has a point.